“Hov, oh, not D.O.C./but similar to the letters, no one can do it better” – Jay-Z

“Who you think brought you the oldies/Eazy-E’s, Ice Cube’s and D.O.C.’s” – Dr. Dre

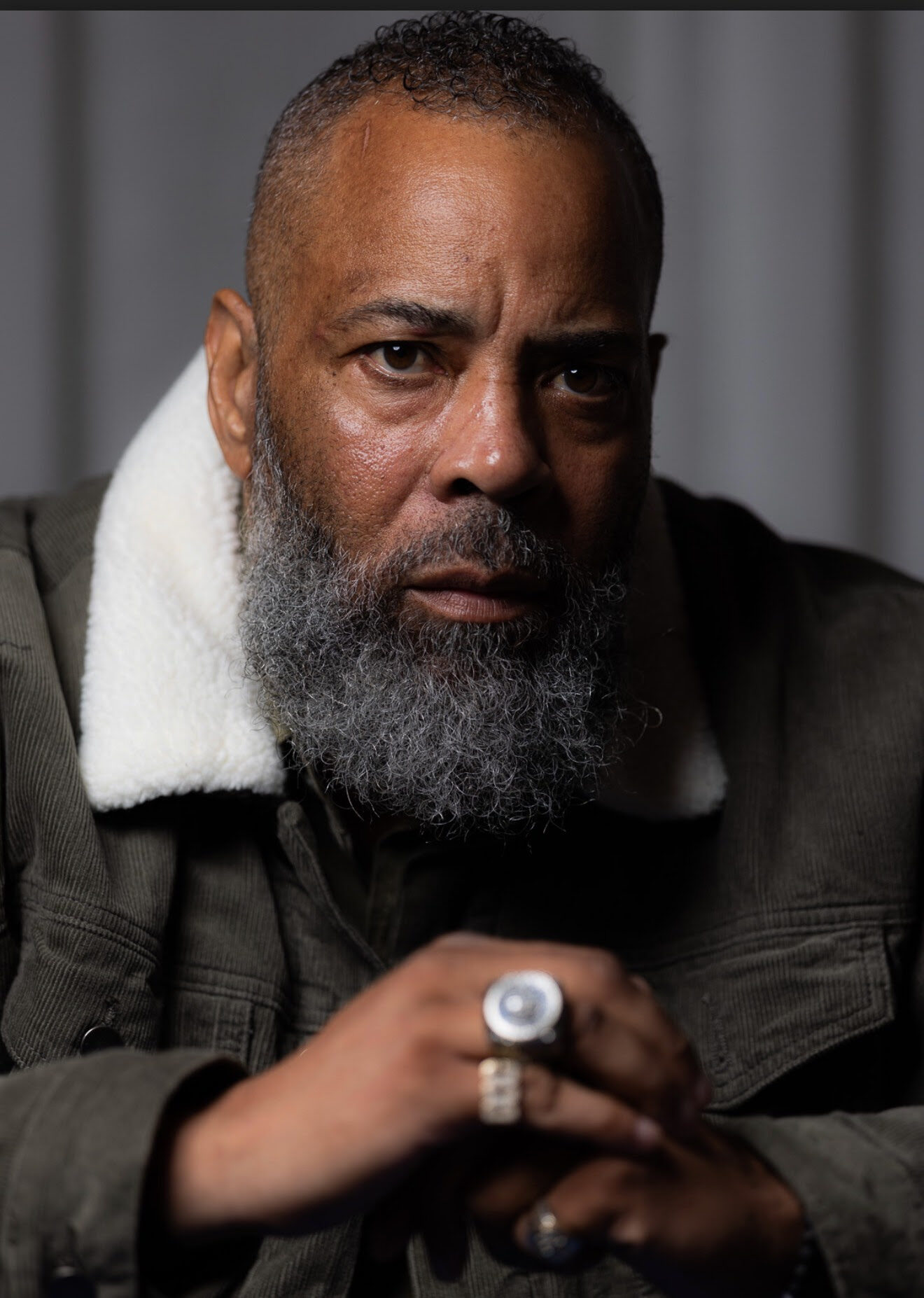

Few figures in Hip Hop carry a legacy as complex, resilient, and foundational as The D.O.C. Long before his story became one of survival and reinvention, he was the quiet architect behind some of the most defining moments in West Coast Hip Hop history — a writer whose fingerprints shaped N.W.A’s rise, sharpened Dr. Dre’s earliest visions, and helped introduce the world to Snoop Dogg’s unmistakable voice.

As the force behind No One Can Do It Better, an album many still consider a gold-standard benchmark of Hip Hop’s golden era, The D.O.C.’s pen didn’t just create hits; it helped forge a cultural blueprint. His influence resonates across decades of music, mentorship, and artistry, making him one of the genre’s most essential and enduring storytellers.

The Hip Hop Museum caught up with The D.O.C. for a rare interview to talk about putting together his classic debut album, the early days of N.W.A., what people don’t appreciate enough about Dr. Dre, his forthcoming new album, and more!

Adam Aziz: How is it to look back today at all the iconic music you’ve made and been part of that in many cases has transcended Hip Hop into Pop culture?

The D.O.C.: It’s beautiful. It’s a joy to see that, and to see what we spent so much of our young energy on trying to build resonates even to this day.

And so the fact that the Museum is finding its place is apropos. It’s time for Hip Hop to be recognized as a classic art form and for us to take it out of the street, if you will, and put it in a place where it could be viewed and acknowledged for what it really is.

AA: Take me back to your debut album, No One Can Do It Better. How did the sound and vibe of that project come together?

D.O.C.: I’m from Texas. I’m a Dallas guy, but I’m really an old-school East Coast guy, like all of my tendencies come from that ’80s golden era, late, mid to late ’80s school of artists in the New York space.

When I came to California, I really brought New York City with me. I was the first New York MC in LA, if you will, and it really didn’t matter what you gave me, I was going to approach it with that vibe, that rock and roll influence, which was from Run-DMC when they did “Walk This Way.”

The Funk on that album was all Dre.

AA: You were a writer and worked on some of the most iconic records. When songs like “Nuthin’ But A G Thang” were coming together and you heard the finished record, did you guys know it was going to be one of the biggest records ever?

D.O.C.: Yeah, we knew it. I knew “Straight Outta Compton” was going to be that. We knew because it was good. The difference between good artists and great artists isn’t being good or knowing when you’re good; it’s knowing when you’re not. I was always really good at knowing when it’s not good and speaking up about it.

AA: We’ve seen the movies and heard the stories, but you being around for the heyday of N.W.A., how crazy was it? How wild was the political backlash against the group?

D.O.C.: I don’t think we looked at it from a political lens. They didn’t want us to do certain records, and depending on their attitude towards us or how they treated us, that’s the way we reacted. So those couple of times, what we did with the music anyway was really because the police or the people, the powers that be in that city, were really harsh towards us and treated us poorly. We were just young dudes trying to make a living and performing art.

In politics nowadays, you can clearly see that most politicians are full of sh*t. Back then, they hid it a little better. They wanted to use us to get better views or promotion for themselves. We were about doing shows and Eazy didn’t give a sh*t about anything. He just wanted to win.

AA: What do you make of how Death Row Records has come full circle with Snoop owning it now?

D.O.C.: I think it’s only right. It’s his energy that made it what it was. Hopefully, he will be able to take away some of the stink that’s on the brand and start doing some positive things with it so it’s not always associated with negative sh*t. Snoop’s an iconic figure. He’s probably a bigger household name than anyone in the game.

AA: What happened to Texas rapper Six-Two? He was one of my favorite artists on Dre’s 2001 album.

D.O.C.: Six-Two is in Fort Worth (Texas). He’s still working. He was clearly one of the greatest to do it.

When I met Six-Two, he was doing what street guys do. The way I described him was if B.B. King made a Rap record. Doing what street guys do, he got caught up in situations, and it’s hard to keep the ball rolling. But you’re absolutely right, he’s one of the best artists to come out of the state of Texas, no question.

AA: Was there ever a Six-Two album made?

D.O.C.: Six-Two’s album was supposed to be an album I put out called Deuce. Dre and I didn’t see eye to eye on it. Dre and I have had some iconic battles about creative direction over the years, and we’ve always maintained our same philosophy: “f*ck you, no f*ck you.”

AA: I was speaking to Mark Batson a while ago, and he said that the closest we will ever see to Dre’s Detox album is the Compton album Dre dropped in 2015. Any records from the Detox sessions that stand out to you?

D.O.C.: No. I hear sh*t leaked all the time. Batson was probably right. What you got with Compton was Detox. But the attitude of that record was different. But as far as the production of that record, it’s the closest you’ll get to Detox.

AA: You’ve spent so much time with Dre. Is there something from a production or creative space about him that people might not know or might not be aware of as other things about him as a producer?

D.O.C.: Most think that Dre is an amazing beat maker, and he is. But what separates Dre from 99.99% of other guys in that spot is not his production skills; it’s his engineering skills. Him behind that board. It’s the way he turns those knobs that separates him from everybody. And it’s so interesting to watch him cause it looks like he’s just doing the same sh*t every time. I’ve been watching him for 30 years, trying to figure that sh*t out. He’s one of one.

AA: In the mid-90s to early 2000s, the West Coast really had it, but then things started to shift to other regions. Why do you think that happened?

D.O.C.: Control and greed. All of those things take away from the joy in creating. And if it’s not fun, then it’s not going to be great. The machine is a f*cked-up thing. And it’s f*cked up the game for a long time and continues to f*ck it up. Like anything else, the machine has had its day, and it is splintering. It seems to be falling apart in places. The big three, if you will, don’t know what the f*ck to do because they never knew what to do in the first place. It’s falling back into the hands of the individual, and these phones give you access to hundreds of millions of people at once.

The dynamics of the game have changed from the machine back to the creator.

AA: Why do you think it’s important Hip Hop has its own physical Museum space?

D.O.C.: Hip Hop is a billion-dollar business. There ain’t no billion dollar n*ggas out there. It’s important because Hip Hop deserves its own space. We need to pay respect to those who paid their lives for it, not those who sit in boardrooms and rape it. It’s disgusting what these corporations have done to these kids, me being one of them.

I’m blessed to have found myself again and to be still able to create. I’m probably better now as an artist than I was in ’89, since I made that first record. So now is the time for a follow-up.

I’m making an album: half this voice, half AI. The first time I perform any of this music will be when The Hip Hop Museum opens.

Follow The D.O.C. on Instagram.