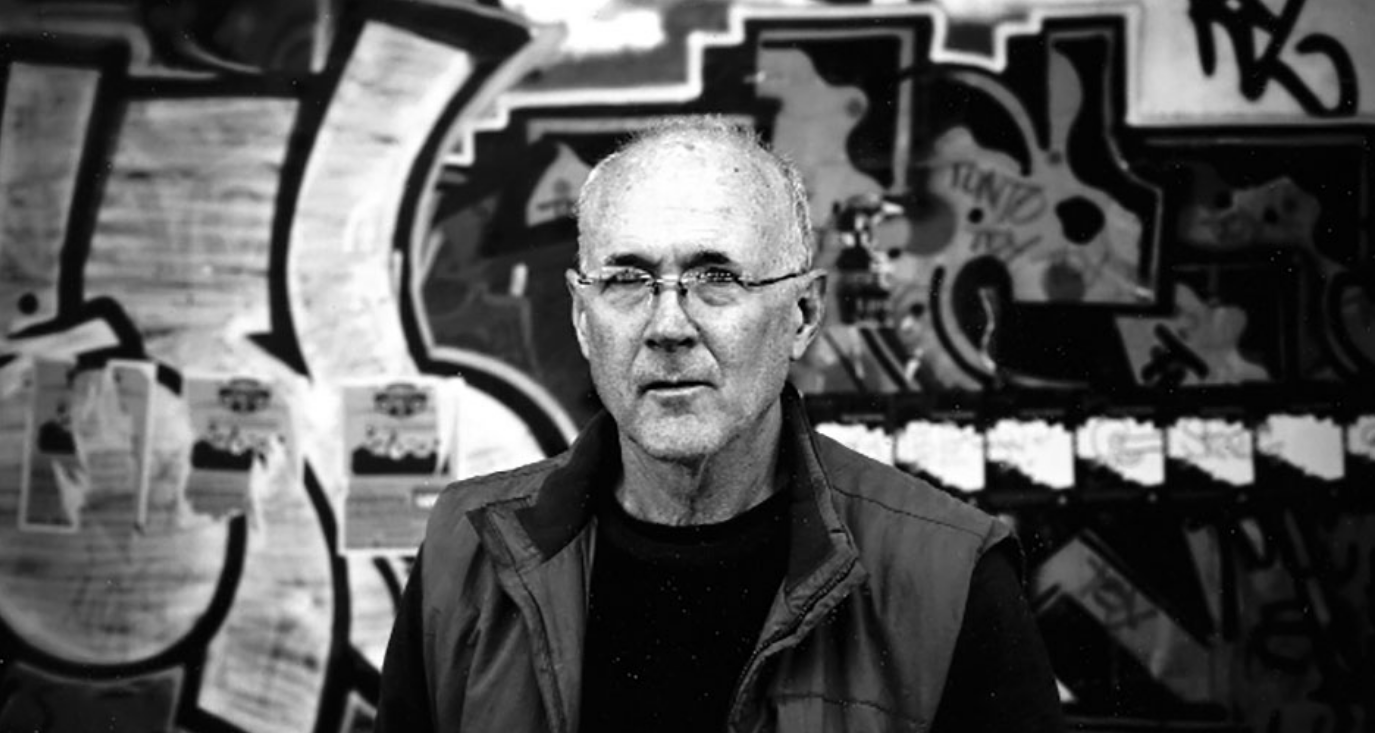

Few figures have captured Hip Hop’s early days with the same authenticity and dedication as Henry Chalfant. A pioneering photographer and documentarian, Chalfant’s lens preserved the raw energy of New York’s subway graffiti in the late 1970s and early 1980s, at a time when the mainstream dismissed the art form.

His work alongside Martha Cooper on the groundbreaking book Subway Art and as Producer of the seminal documentary Style Wars didn’t just document graffiti, they legitimized it as an essential element of Hip Hop culture.

Beyond graffiti, Chalfant’s archives form a vital visual history of breakdancing, fashion, and the everyday spirit of Hip Hop’s birth era. His work stands as both an artistic achievement and a cultural record, bridging underground creativity with global recognition.

Now 85 years old, The Hip Hop Museum caught up with Henry Chalfant for a rare interview to talk about Hip Hop’s early days, the making of ‘Style Wars’, how his relationship has changed with Hip Hop culture, and much more.

Adam Aziz: As someone who got involved with Hip Hop culture so early on, what do you make of Hip Hop culture today?

Henry Chalfant: Hip Hop today is a variety of things. There are different elements of Hip Hop, and I think it’s important to make that distinction. I think the music industry has made it altogether something different with the incentives of the market. It’s such a big deal. And it has become a worldwide phenomenon, but it was already becoming a worldwide phenomenon when, in the early days, the youth in these different parts of the world saw what people, especially kids in New York, were doing, and were very drawn to it. It was very inspiring to people all over the world.

And who knows why? I say that jokingly. It’s pretty clear because it was so cool and it was theirs. It’s something that they invented. And it was in their adolescence that they invented it. And that was very compelling to other adolescents all over the world.

AA: How has your relationship with the entirety of Hip Hop changed as you’ve gotten older?

HC: I think in the beginning, I was drawn to the complete invention of every aspect of it. The fashion was very, very specific, but made up of available objects for sale. And they made choices, kids made choices, which became the standard.

In the early 80s, when Hip Hop started going around to Europe and to California and other places, kids from those places would visit New York, and they had my contact. So they would visit me, and I made many, many trips to the Bronx to find the people who made the belt buckles where you could put your own letters on the buckles. That was one of the major things, obviously, the sneakers, the shell toes.

These things were invented by kids and then it became a style and then they became marketing targets later on for cool things to wear and I guess once you, it must have something to do with the music industry people, stars would wear certain things and that would be a trend.

AA: When you were making ‘Style Wars’ in the early ‘80s, could you see what the monetary aspect of Hip Hop culture would become? Or was it still too early on?

HC: In the early ’80s, it was still too early on. We had no sense of it. It seemed to be a very local thing. And then California became another part of it. And then there were successful albums associated with successful rap groups. But it still seemed local.

I remember when I first met Rocksteady Crew, and they were eager to make some money. I tried to interest corporations, including McDonald’s, but no one would bite.

AA: When ‘Style Wars’ came out, it was at a time when Graffiti was still vilified. What was one of the most interesting or unique interactions you had with people outside of the Hip Hop world when the film came out?

HC: When the film came out, one of the first screenings we had was at the Margaret Mead Film Festival, which is held at the Museum of Natural History on an annual basis. The audience was divided between people who said it was nothing but vandalism and a crime, and others who said it was art. That was a memorable occasion.

On another occasion in the early 80s, I thought there was an opportunity to monetize the train around a particular graffiti piece and make a postcard out of it. The first time I tried to do it I took it to The Museum of Modern Art and said, wouldn’t this make a nice postcard you can sell? We could share the proceeds with the artists. They liked the idea and said they would have to take it to the top brass. I came back two weeks later, and they said no, it’s not going to fly. I asked why, and they said they showed it to the elderly Head of the Board of Directors, and she said that the people who did the pieces should be lined up and shot.

AA: Today, we see street art pieces selling for millions of dollars and appearing in galleries all over the world. Do you see today’s street art scene a continuation of the graffiti movement or has it split into something completley different?

HC: It’s quite different from the graffiti movement. It shares elements of it. Mainly the element of doing it on your own volition.

The street artists I know who do work on a basis of getting paid for it and doing it legally still want to do it illegally because there’s more freedom. They tell me they love the feeling of being free and being able to paint what they want. When you get into situations where you’re paid to do it or you have permission to do it, there’s always a framework and limitation. The only time they’re really free is when we run around at night.

AA: In ‘Style Wars’, New York City is the backdrop for the film, but the city almost becomes a character in its own right. Was that intentional, or did it just happen naturally while shooting the project?

HC: Here’s how it happened. Had I made the film by myself, it would have been nothing like that. It would have been more of a portrait of the graffiti writers.

I was working with a filmmaker, Tony Silver, who was the Director. It was his vision that it should be more than just about kids painting a train – that was the meaning of ‘Style Wars.’ The battle between the kids and the Mayor. The kids and the Transit Authority. Tony saw it as a story set on a huge stage with New York City as that stage, so that’s how it happened.

AA: The pacing of ‘Style Wars’ is almost musical in how it flows. How much influence did Hip Hop beats and breaks have on the way ‘Style Wars’ flowed?

HC: It influenced it. Sam Pollard was the Editor. He was an amazing, gifted Editor. I had a hand in choosing the music, but Sam made sure it all flowed well. It’s done with a wonderful, rhythmic sense. I chose a lot of the music based on my own taste.

AA: What is one of the biggest misconceptions that people still hold about graffiti’s place within Hip Hop culture?

HC: Graffiti isn’t a perfect fit over Hip Hop. The kids who grew up in the early days of Hip Hop grew up with graffiti, and they see it as one in the same. They would break, they would paint.

But not everybody who was doing graffiti necessarily responded the same way to Hip Hop as a whole. There were kids from Washington Heights. And some of the originators, like Taki, he was a Greek kid. And the people I knew, like Seen from the East Bronx, weren’t into Hip Hop at all.

AA: Who is the greatest graffiti artist of all time?

HC: That’s a crazy question. I have my favorites. There are so many different talents and skills. Some are attracted to muralism. Some invented writing styles—Phase 2. TMT had an enormous influence. And then there are people like Blade who are completely wonderful but have their own way of doing things.

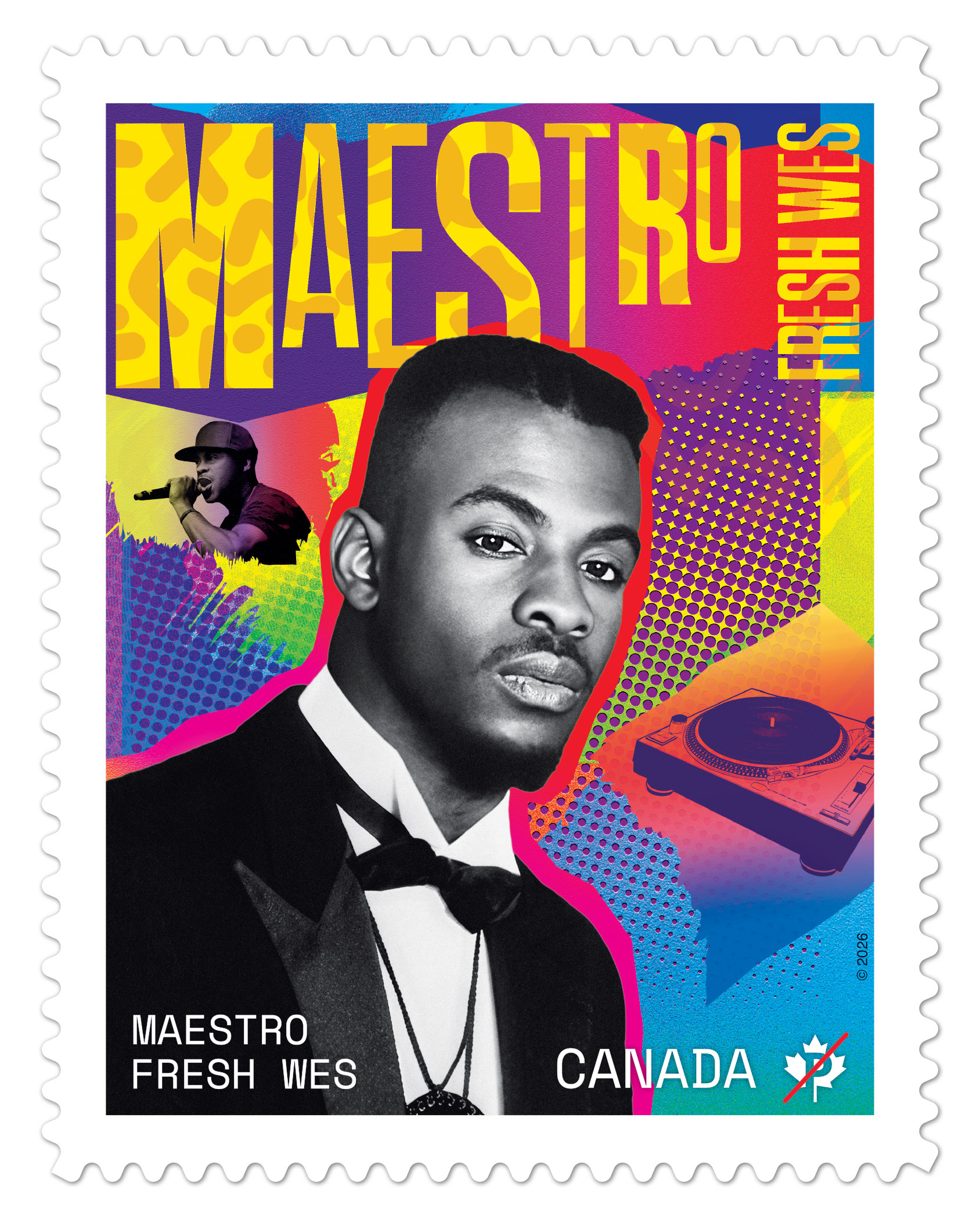

AA: What will it mean to you to see The Hip Hop Museum open in the Bronx in 2026?

HC: I’d say it was where it was meant to be. There have been all kinds of proposals for graffiti museums elsewhere. There is a very good one in Florida. They’re fine, but there always needed to be one in New York. I’ve been waiting.

Follow Henry Chalfant on Instagram.