Your cart is currently empty!

Block Party: Hip Hop’s 50th Birthday Jam

Aug 11, 2023 @ 12:00 pm

Generation X, Boomers, and those who preceded us are sure to recall one specific thing that was not included when learning about artists in school: why they painted, drew, photographed, and sculpted. Today it’s called one’s origin story, or their “why”. As strange as it may seem, there was a time when the artists whose work was the foundation of the curriculum – the Impressionists, Expressionists, Art Nouveau, and styles taught in art history classes – were presented as makers of art. Period. This, of course, reflects what was actually captured in history and what was available via research (read: there was no social media in the mid-20th Century, 1970s-1990s) as it does about academia and teaching.

Later on, and today, when it comes to Jean-Michel Basquiat, those responsible for Pop Art, such as Keith Haring and Andy Warhol, and modern artists like Takeshi Murakami, Mark Bradford, and Cindy Sherman, interviewers share what was happening in the world when they made art. Or the artist has so much personality, to exclude their quirks, quotes, and fashion style would limit their art’s impact.

To know the artist is to know their work. We know this now, and we are grateful for what awareness of who an artist is does for our experience with and enjoyment of their creations.

When Johari Commodore and Jaiya Chambers, the older sister and nephew of Tarikh Commodore, generously donated 11 of Tarikh’s drawings to the Universal Hip Hop Museum, we were grateful beyond the obvious reason (significant works that will live in the museum’s collection forever and be experienced around the world). They gave us an opportunity to introduce to the world Tarikh, who passed in 2013.

The Bronx in the 1970s, as much as it was burning (due to arson fires set, many believe, by landlords to their managed properties) and redlining (a post-Depression era act that categorize neighborhoods based on residents’ races, determining them “high-risk”, and denying them housing loans), the communities worked to rebuild both structurally and culturally what had been destroyed. (To learn more about this, I encourage you to watch Decade of Fire, a thorough and thoughtful documentary directed and produced by Vivian Vázquez that was released last year.) Crisis yields creation as much as it generates clarity. That Hip Hop was born in the Bronx in the 1970s is not only appropriate, it’s synchronous.

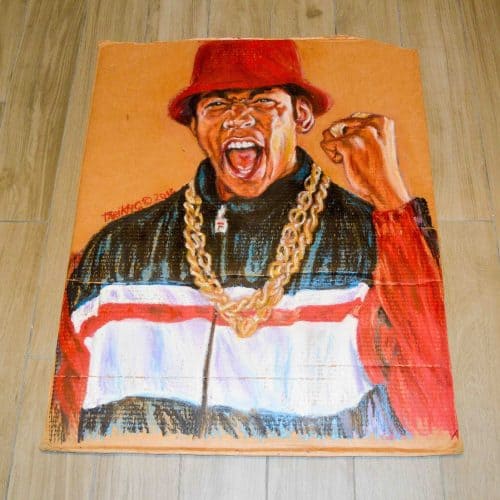

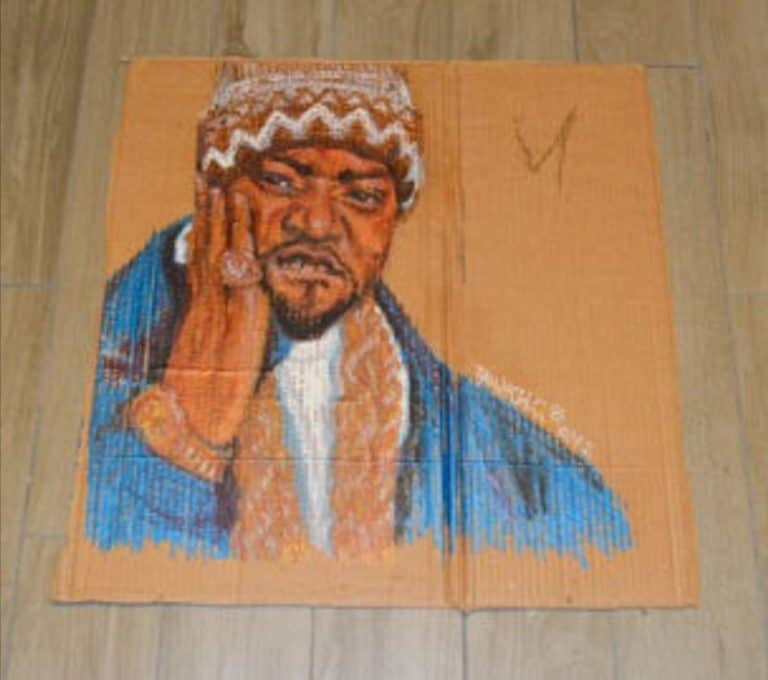

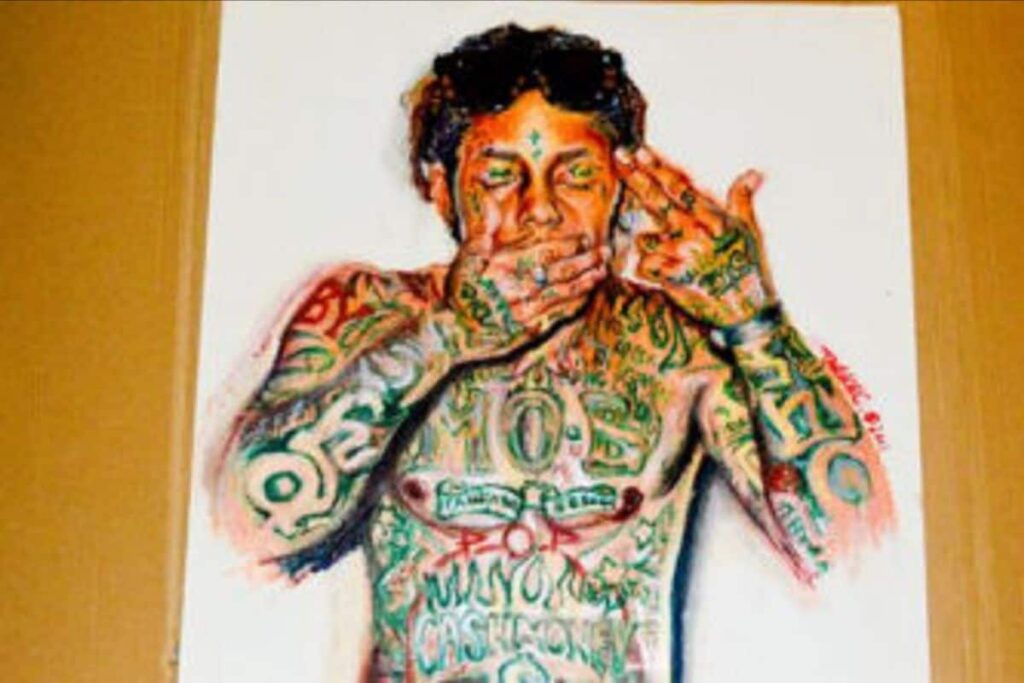

Tarikh Commodore, like Hip Hop, was born in the Bronx. Coming into the world in 1974, Tarikh grew up surrounded by and immersed in all of Hip Hop’s seeds and roots: real life experiences forced upon us and generated by us. Fundamental to Tarikh’s paintings was the canvas upon which he chose upon to draw: cardboard. Tarikh drew and painted on cardboard because breaking, also known as b-boying, is not only a style of street dance originated by New York City youth, it is one of the five elements of Hip Hop. Movies like Krush Groove inspired Tarikh to extend and honor breaking’s impact. Tarikh made cardboard his canvas to support and celebrate how b-boys moved and danced on cardboard on the sidewalks and in the streets. People draw and paint on any number of reclaimed materials, and Tarikh chose something truly unconventional for his canvas: cardboard.

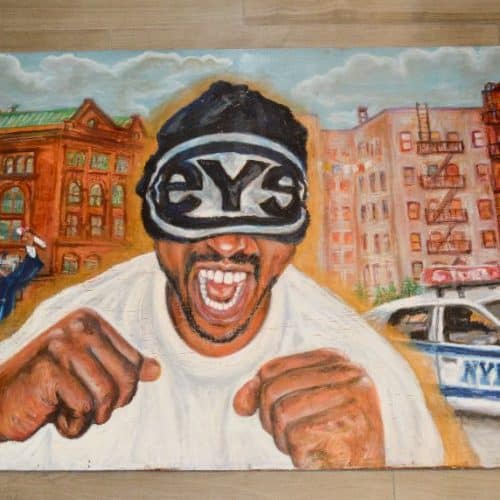

Tarikh matriculated not far from where he grew up. He studied art at both LaGuardia High School and Cooper Union, graduating from each. While he was born with the artist’s gift, he was committed to becoming an artist, which was what he loved most. He chose to draw artists like L.L. Cool J, the Wu-Tang Clan, and their performer cohorts who – through their beats and rhymes – chose to speak about the real situations experienced by Black people. Tarikh wanted to keep those stories going for and leave impressions on audiences long past those who heard “Radio” and “Enter the 36 Chambers” when they were released. Hip Hop, and his love of it, was the key origin of Tarikh’s art. He was drawn to it because, of all the music to which he had access, nothing expressed his culture and his community’s culture like Hip Hop. He heard lyrics, they spoke to him, and he drew the people who rapped them.

While Tarikh’s passing leaves a story unfinished, he did us all an honor by making so much artwork. We will keep you aware of future developments and media regarding Tarikh Commodore. Thanks to Jaiya Chambers and Johari Commodore for their contributions to our feature.

"*" indicates required fields

Copyright © 2024 - The Hip Hop Museum | Powered by Growth Skills