Your cart is currently empty!

Do you remember what came effortlessly to you when you were growing up? You know what I’m talking about: easy and fun, something that allowed use of your inherent skills, and possibly gave you the opportunity to create something or a new way to do something.

Did you decide to dedicate the energy, effort, and time required to make this native-to-you talent a series of skills, and via these skills you’ve made a profession? What does your life look like?

Antonio Mcilwaine, the fine artist known as ARM OF CASSO, can answer all of these questions with ease and truth: “I felt like art was one of my superpowers. Visual art came to me like second nature. I started art because I failed a test in kindergarten.”

When Antonio applied to kindergarten, he failed the first drawing test. From that moment, sparked by his father’s pressure, Antonio practiced, watched cartoons, studied comic books (including Captain America and Batman), and drew. The school let him take the test again, he passed, and he enrolled.

“And that, pretty much, led me on the road to become an artist,” he told me wholeheartedly when we spoke.

The competitions and contests Antonio went on to win from age seven were not one-offs. What began as something he did to comfort himself – drawing – became a skill acknowledged and recognized by the larger community. When Antonio was eight, Philadelphia’s KYW-TV aired a segment detailing how the school district wasn’t providing enough money to the schools to buy art supplies; the b-roll was of Antonio drawing.

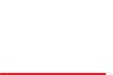

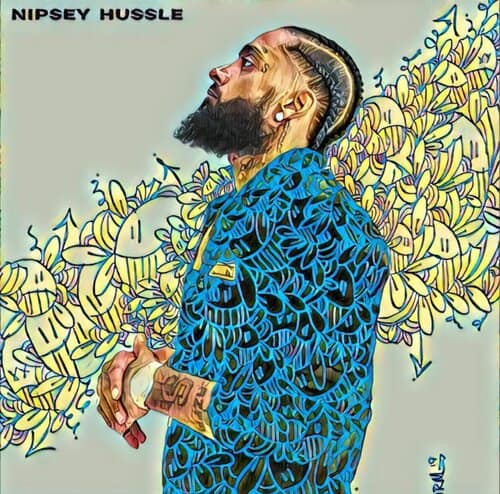

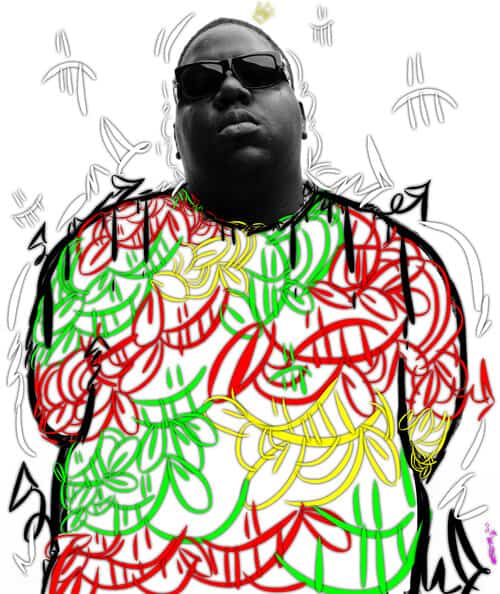

drawn by Antonio Mcilwaine and donated to the Hip Hop Museum

Flash forward to 1999 when Antonio is accepted at CAPA, The High School for Creative and Performing Arts in Philadelphia. High school is intense enough, between the higher academic expectations, opportunities to participate in athletics, the arts, and afterschool programs, and the always pending what you’ll do when you graduate. Add to that living in an underserved, dangerous neighborhood in a house without furniture. Add to that the murder of a loved one whose killer is never found.

Antonio’s Uncle Doug, his father’s great uncle, was robbed and murdered in an alley behind the family home. He was shot in the face with a sawed off shotgun.

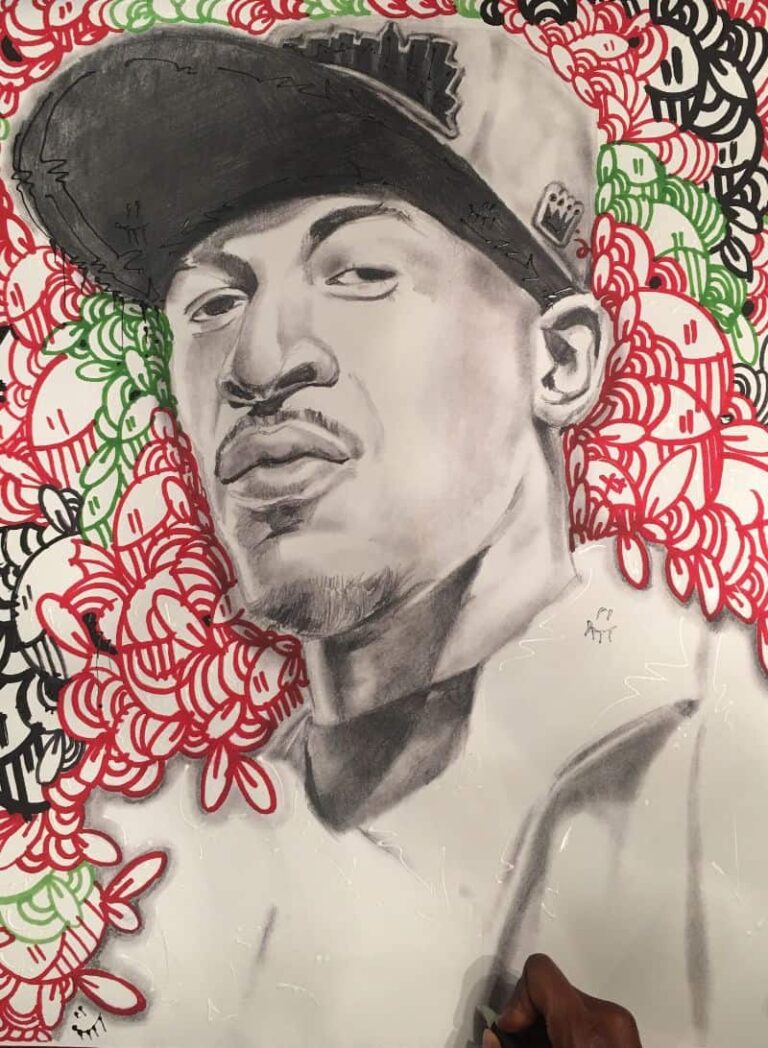

I learned this from Antonio while we discussed the artists, albums, and songs that resonated most with him. He said, “I’m a big Tupac fan, so ‘Me Against The World’ and ‘All Eyez on Me’ are real. When my uncle was murdered, ‘Pac’s album – Me Against The World – was out, and its songs ‘Death Around the Corner’ and ‘Lord Knows’ really got to me. I could feel what ‘Pac was speaking about, because not only was death around the corner, it happened in my backyard.”

(18″ x 24″ digital print on canvas with acrylic embellishments)

This trauma was devastating. Antonio applied his drawing skills to his life immediately following his uncle’s murder, and turned his trauma into work. “My art teacher said that the faces in my sketchbook were all angry,” Antonio remembered. “I painted a figure in a straitjacket, bullets, and skulls on a pair of jeans I wore all the time. There was so much detail, and the detail came from my anger and pain.”

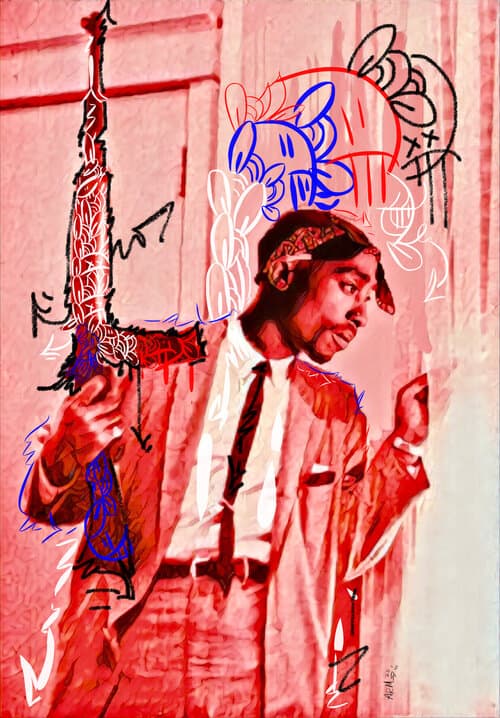

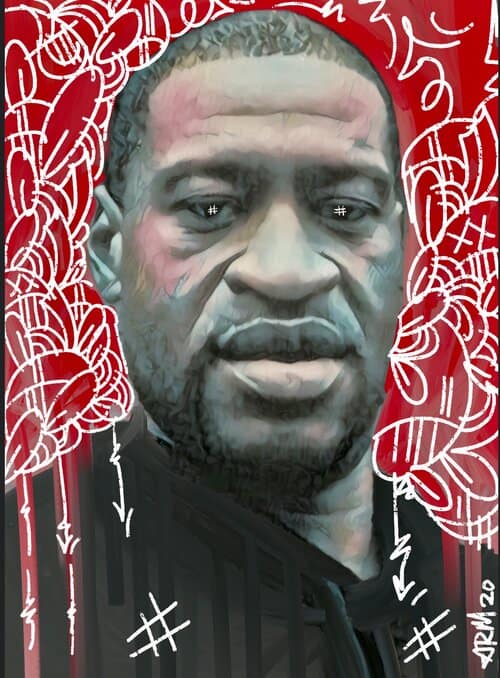

He went on to tell me how it was ironic that those jeans led to jobs. Irony, perhaps. Truth, absolutely. “I made commissioned pieces on jackets, paper, and canvas. With those jeans, I had told a story: the story was built from my emotions, my uncle, and my living conditions at the time.” 21 years later, motifs of grimness and death are found in Antonio’s pieces. Not only do they reflect and are imbued with what happens far too often in the United States (most recently the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd), they are fueled by Uncle Doug’s murder.

(18″ x 24″ digital print on canvas with acrylic embellishments)

Professional artists find their signatures, in autographing, branding, and technique. Antonio’s signature technique is Sharpism. Incorrectly called “doodling” by many people, Sharpism is a method created by surrealist pop artist Travis Moore. Named for its original use of the marker brand Sharpie, Antonio’s Sharpism delivers precision, control, and dimensions that underscore the permanence of the drawing. Since migrating from pens to markers, he has become a master of Sharpism. This method makes his work stand out both for the visual results and its infrequent usage compared to oil, acrylic, and spray paints.

(18″ x 24″ digital print on canvas with acrylic embellishments)

We discussed what Antonio would have told his younger self while he was on the come up. When he told me “Find my niche and style earlier in life,” I asked him why he hadn’t done that, for all his obvious confidence. He replied, “What prevented me from doing those was I didn’t know my identity. I was around other artists and, when someone asked us to draw portraits, we would draw portraits. Today, when someone asks me to draw a portrait, I explain my motif: abstract, socially involved, and detailed. If they don’t want that, they find another artist.” What Antonio called niche and style, this writer identifies as self-awareness that only comes from experience lived, actions done, and things made.

Philadelphia. If there was ever a city ideal for creating, developing, and launching something, Philly is the place. Be it music, food, or art, this town is the birthplace for icons and landmarks. For Antonio, it was a great city to begin an artist’s life. “I had gone to CAPA, which gave me the foundation for drawing commissioned portraits, it provided opportunities to develop further what had begun when I was five years old. I learned a lot from artists and teachers of my craft. I met many singers, rappers, and actors that I was able to build great business relationships with.”

Upon graduation from CAPA in 2003, being a visual artist was an obvious thing for Antonio. And as is the case for many artists, another mode of art appealed to him: Hip Hop. “I always wanted to be a painter,” Antonio asserted, “And before I chose painting for my profession, I was a rapper. I paid for studio time and equipment, I recorded CDs, and my performance name was Tone Casso.” Visual art, though, was never far from the recording studio. “While I was rapping, people would ask me to draw something. Every time I would be commissioned to draw a portrait, I’d get paid.” Since he was a child, visual art had been second nature. “Rap and Hip Hop music did not come naturally to me,” Antonio stated, “I picked up rapping and had to fine tune it. I tried to make things happen quickly, which portrait drawing always did, and rap wasn’t that way.”

The a-ha moment for Antonio came when he realized his inherent skill – drawing – was not only rooted in what he truly cared about, it made possible getting paid. Consistently. Always.

Antonio’s move came in the form of his own expectations sparring with the rhythm of the music business: “In 2003, I felt that being a recording artist in Hip Hop had an expiration date for me. By a certain age, I needed to have things in motion, meaning music on the airwaves. I had nothing on the radio. One of the reasons I chose to become a visual artist is I was paid to make something that came easily to me. I could always create the product. Always.” The product was the portrait. He enjoyed it. Using different techniques. Telling a story. And when he finished, he could look at the portrait and say, “I created this.”

Spoken like a real artist.

(18″ x 24″ digital print on canvas)

He moved from Philadelphia to Miami in 2016. “In Miami, I saw that everyone – including artists – was celebrating and expressing their culture: Jamaicans, Haitians, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, as well as Black people. I was encouraged to celebrate my culture, and I felt I needed to do it. I love Hip Hop music, and that is why I paint so many Hip Hop artists.” Antonio remembers his early days in Miami: “Every artist had their niche and style, and I knew I had to find mine. While living in Wynwood, the art district, for a year, I studied every wall and every artist. The neighborhood was full of galleries and spaces for graffiti. It was an amazing time to create and network with so many different cultures.” During two years of vibing and interacting with the culture, his color palette expanded, his mind opened, and he created his brand. Antonio found his style.

Today Antonio lives with his wife and daughter in Atlanta.

Like it is for so many of us, Hip Hop was and is a bridge for Antonio. What it bridges for each individual is specific to them: history, culture, politics, personal life, mental health, truth, style, and a myriad of things. Among the truly resonant moments in Hip Hop for Antonio are rap battles. Each one, in its way, changes the face and trajectory of Hip Hop. One of the battles that left a significant impression on Antonio is 2001’s between Nas and Jay-Z. Mr. Carter was at the top of his game when Nas called him out repeatedly in “Ether”, one of Stillmatic’s tracks. The feud between the two kings was resolved, and Antonio captured the ethos and illustrated the complexity between them in this painting, The Greats.

(Digital art 18″ x 24″ Print on demand)

For young people who want to make art and are, as he is, inspired and empowered by Hip Hop, Antonio brings every form and fashion of Hip Hop to his work. “Our youth needs to be able to express themselves in constructive, not destructive, ways.” Antonio has made it his responsibility to express his culture through drawing and painting because “I know the history of America and I live in the present time. I want to show people that Black people have real intellect and skills, and we do far more than the bad things reported. I try to present these truths and share these messages through my art. God gave me a talent, I’ve worked to make it a skill, and it’s crucial that I share what’s not being talked about to heal, and to make people happy.”

And regarding today, in light of all the wrongful deaths and intentional harm done to Black and Brown people, Antonio said, “For every statue being taken down, when it comes to real change, I want to see actions. Promises, broken promises, like the ones shouted by our government aren’t enough. We have to keep demanding change, and making change; we cannot wait for the government. As laws, such as cops not using the chokehold, are rewritten, it has to be acknowledged that this wouldn’t have happened had we not protested, shown videos on social, and made clear that we will not stand for this. And our actions have been showing that and they will continue to show it.”

As it was sung in “Hamilton” it’s not a moment, it’s a movement. Antonio’s work and his actions are driving the movement.

You can see the painting he donated to The Hip Hop Museum – Rakim: Hip Hop is Still Living – before we break ground; it is the first drawn image in this article. Check out Antonio’s work on his website, Facebook, and Instagram and see how he is as much an activist as he is an artist.