Your cart is currently empty!

What’s Important About These Items

Do you believe in coincidence, happenstance, or things happening in a seemingly random way? This author does not believe in these. Things happen when they happen for reasons not always immediately known. And it’s this belief in synchronicity that underscores what I call intended miracles, one of which was definitely in play when legendary photographer (and THHM donor) Michael Benabib chose to walk from his home in Greenwich Village to his studio in SoHo in 1988. The day he chose to walk past 298 Elizabeth Street – the original location of Def Jam’s office – was the day the game changed. About this spot in Nolita, Michael told us, “Every day in front of the door, there was a scene. It was always full of B-Boys, MCs, and rappers. And I always had my camera. I photographed and got to know everyone. Kurious Jorge [Spanish Harlem-based MC with significant lyrical skills] showed my photos to Russell Simmons. I sent photos to Russell. And, I got a call the next day to photograph him for a promotion. That’s how it started.”

Not too shabby. Definitely not random.

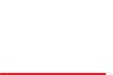

photograph by Michael Benabib for Def Jam

During the mid- to late 1980s, Hip Hop was booming. Our curators captured some of this at [R]Evolution of Hip Hop 1986 – 1990 Hip Hop’s Golden Era (whose grand opening was June 28, 2022), and Michael lived it. Like many visual and performance artists, he worked on speculation, or “on spec.” In the best, most hopeful ways, photographing on spec means – according to the AIGA – to photograph without being hired in anticipation of being paid for the shots. This is an unpredictable way to generate any revenue, and even the most skilled artists risked theft of intellectual property. While the game is different today, between phones being used as cameras and social media providing opportunity for everyone to be their own publicist, when Michael was cutting his teeth as a professional photographer, he did his share this. About his, for example, pics of DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, he would contact Right On! and The Source, and he would present the work for publication. He did this for many artists and would follow the shoots with calls to their PR representatives, and offer to officially photograph the subjects. Before we could discuss how risky this was, Michael declared that it was tantamount to a gift, “being able to experience this culture – Hop and all that it was – and photograph it.”

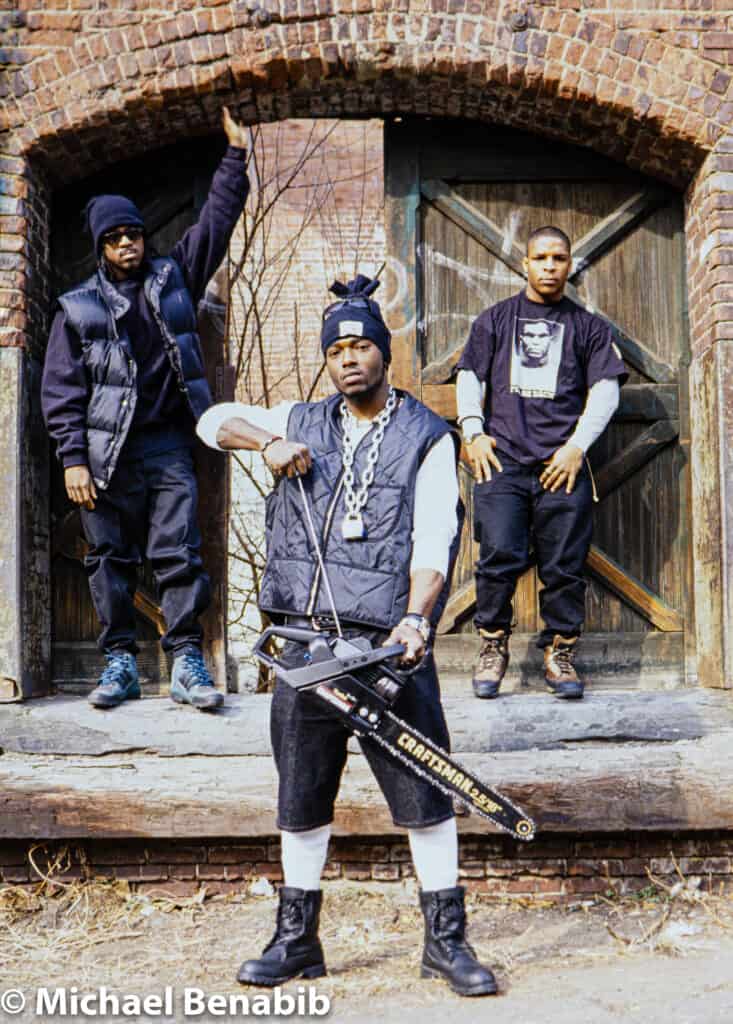

photograph by Michael Benabib for Atlantic Records

Why Michael Donated These Items to the THHM

We ask every donor – if they don’t tell us at the jump – why they are giving to our Archives and Collections. Michael shared, when asked, “Because it’s specific. It’s a collecting house. I think the The Hip Hop Museum is going to be the place for researchers, fans, and artists.” When we talked about what music means to people, he told us how the COVID-19 pandemic presented an expected response. During the worst of the shutdown, “For the first time, I was shooting every day in my studio. Also, for the first time, I organized these photos. All kinds of people came to my studio. I was really grateful to see them react, laugh, and recall, and hear what these photos meant to them.” So, he chose to bring that feeling of meaning to the THHM. To look at a photograph of a beloved MC, DJ, beatboxer, or dancer reminds us how “fans in the audience know every word and every line in the song.” That’s a kind of resonance only possible when there’s heart in the work. You can’t miss it, and you can’t fight it. There’s a whole lotta heart in Hip Hop.

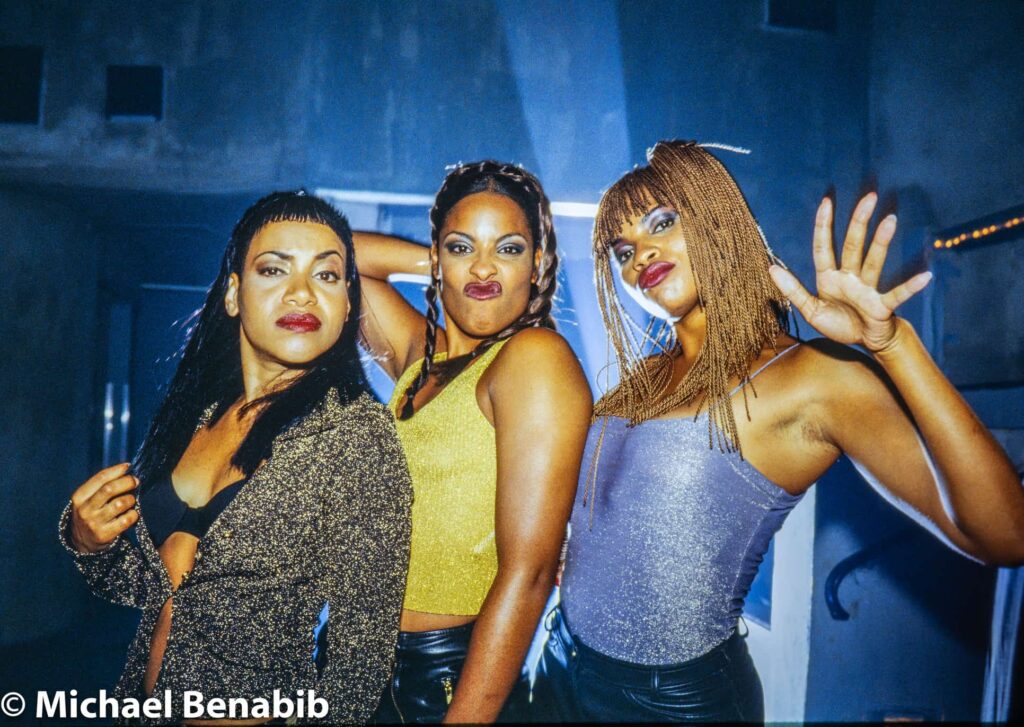

photograph by Michael Benabib for, and published in, Right On!

Michael told us that every photo has a story behind it. The story is comprised of people showing up late, the weather not cooperating, and always a little drama. These things, however, only contribute to the making of a terrific visual story. For people to experience the history, inspiration, and culture of Hip Hop, seeing the photos, watching the videos, and reading the interviews are one component. And to know the origins, behind the scenes, and intentions of what they’re experiencing is how the The Hip Hop Museum is setting itself apart from the existing locations dedicated to Hip Hop.

Michael started shooting photos at age 14, which resulted in his falling in “love with the camera itself.” He committed to using the “magic box” to take photographs of things and people that resonated hard with him. We can see the results of his decades-long hustle that, today, comprise a remarkable collection that he “wants out there and noticed.” Like the best of artists, Michael is humble: “Being a photographer is something I always did; I never thought people would care.”

Not only do we care, we admire. Also, we are inspired.

photograph by Michael Benabib, on spec, and published in Entertainment Weekly

In Michael’s Words

“I feel like Hip Hop picked me. It presented itself to me on the street. This movement picked me because of the way I experienced it on the streets of New York. It was such a dynamic force in 1985-1986. I was compelled to start taking these photos. Because it was happening. It was vital. It was coming out of the speakers. Kangol hats. It solved the problem that every artist has: where are you going to point your camera? I was in the right place at the right time. And I ran with it.” – Michael Benabib

photograph by Michael Benabib, on spec, and published in Rolling Stone

Besides the photographs here, you can keep up with Michael on the socials (@classichiphopartists and @michaelbenabib on IG and @michaelbenabib on Twitter) and, before the THHM opens in 2024, in the books In Ya Grill: The Faces of Hip Hop and Smithsonian Anthology of Hip Hop and Rap.